Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time in a Roman house. Specifically, I’ve been processing archaeological finds in the corner of a Roman garden in Pompeii. With this in mind, I thought it would be fun to think about a typical Roman home both in terms of floor plan and functionality. We’ll do just that in today’s newsletter!

Before we dive in, here are some things to keep in mind.

Although many Campanian houses share common forms and spaces, each urban domus (plural: domi) is unique. Depending on previously extant architecture and the needs of a patron, domi vary! This newsletter will focus on the common threads between these domi, particularly spaces preserved on their lower floors (second floors don’t survive in Pompeii).

Most Romans did not live in or own such domi. Although the domus is often taught as exemplary models of Roman housing (especially from an Art Historical angle), sub-elites did not own grand abodes. Indeed, many residents of Pompeii (and other Roman cities) lived in apartment-like structures often called insulae.

Whereas today, we typically assign domestic rooms singular and set functions, Roman houses worked a little differently. Many rooms had fluid functions. They could be used for sleeping, storage, or hosting guests as needed.

Day-to-Day Life in the Roman Domus

Before thinking about the physical space of a domus, let’s talk about some of the social and functional processes that occurred within these spaces. The domus was a place where owners, families, enslaved people, clients, and even patrons engaged with each other, larger social networks, and practical tasks each day. Based on some common finds in domestic spaces, here are just a handful of things that went on in a Roman domus on any given day.

Loom Weights and Spindle Whorls

Loom weights and spindle whorls are among the most common objects found in domestic contexts across the Mediterranean, and in Pompeii! They point to an important functional and social practice in the home: textile manufacture. Roman women, like their Greek counterparts, engaged in textile work for both practical and social reasons. Practically, members of the household needed clothing! Socially, weaving and thread-making were ways for a woman to perform her virtue and piety.

Textile work could have been undertaken by a matrona, an enslaved woman, or a young girl. Of course, the practice had different connotations and conditions across classes, but it was not inherently an activity limited to a particular social group.

Terra Sigilata Vessels and Fragments

Terra Sigilata, or burned earth, vessels were used during the convivium, or banquet (see the red-orange vessel on the table above). Vessels survive in many forms, each having a specific function. Some were used for drinking, others were used for mixing and serving. Banqueting was one of the most common, recurring social gatherings in the Roman domus. Of course, people needed to eat! However, these rituals were also an opportunity for social posturing. House owners could invite their clients or patrons to discuss business, politics, and knowledge.

Painting Pots and Pigments

The earthquake of 79 AD was the most catastrophic natural disaster to hit the city. However, it was by no means the first. In 62 AD, the city was struck by a massive earthquake, severely damaging public and private buildings. Based on the frequency of painting pots in the archaeological record, we can surmise that many domi across the city were currently undergoing restoration and/or repair in 79 AD.

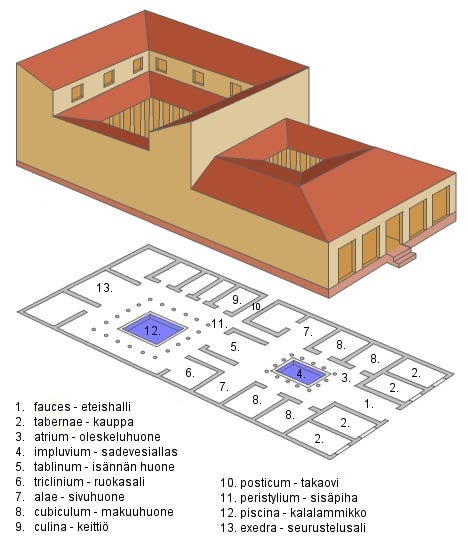

Entering the House: The Fauces

The domus’ entryway, or Fauces (1), was a space intended to make an impact. Both residents and guests entered here, so this space was designed to impart some visual message to passersby. You may already be familiar with the infamous ‘cave canem’ mosaic, the first thing encountered by visitors to the House of the Tragic Poet. In this nearly monochromatic mosaic, a fierce dog seems to be restrained by a chain-link leash.

With his teeth bared and ears alert, the floor-bound canine looks nearly ready to launch at an approaching foe. The text below his feet translates to ‘Beware of the dog. On a practical note, this mosaic warns visitors about a fierce beloved friend. Simultaneously, the mosaic imparts a sense of fear and peril for a new visitor. A prospective client may fear the power of his host or simply may want to avoid a deadly bite.

Not all entryways were quite so vicious. In the House of the Dioscuri, the fauces flank an entering person with each of the twin sons of Jupiter. As anyone (even modern visitors) walks into the domus, the twins stare with large, beady eyes. They stand next to their horses and hold instruments of war. The Dioscuri, also known as Castor and Pollux, had many connotations in Rome, but were often considered to protect travelers. So their placement in the doorway is quite practical. However, unlike the barking dog, they do not warn. Instead, the twins protect those leaving for long journeys and are likewise benevolent protectors of those returning.

While an entryway may seem boring, a domus’ fauces are a space meant to engage with people entering and exiting. The visual and spatial arrangement of space sought to impart certain emotions and thoughts, priming the viewer for their time in (or out) of the domus.

The Atrium

Upon crossing through the fauces, a visitor was granted a view of the atrium (3), where a shallow, often square, pool called the impluvium (4) sat below an equally sized hole in the roof, the compluvium. To a modern viewer, such a setup may seem bizarre. Who wants a gaping hole in their roof? However, for the Romans, this was a practical, functional design.

Predating the popularization of piping systems, the impluvium-compluvium duo was used to collect rainwater for drinking, agriculture, and other practical purposes. Simultaneously, the gaping hole helped circulate light and air into and around the domus.

However, despite the very practical nature of their design, Atrium spaces in domus were also used to impress and dazzle visitors. Oftentimes, despite their direct exposure to the elements, atria walls were elaborately decorated with fine fresco and elaborate visual programs. I was particularly enjoying my time in the atrium of the House of Menander, where fourth-style paintings adorn the high walls.

In addition to the frescos, we often find domestic altars (also usually decorated by painting). These architectural features give us an idea of the experiences that residents and visitors had walking through and spending time in these spaces. My initial description suggests that these spaces were utilitarian and (maybe) social. But the sacred dimension of life in the Roman world was also present… sacred and secular did not exist in the binary within which we speak of them today.

Tablinum

When clients entered the domus to meet with Patrons, they would typically make their way to the tablinum (5). The tablinum can be described in simple terms as the office of the domus’ owners. It was usually situated between the Atrium and the Peristyle. It was a space replete with light, a passageway for a light breeze. With the nearby green space, we can imagine verdant sightlines and refreshing scents wafting through the air.

Based on evidence from the Villa of Papiri in Herculaneum (not Pompeii, but nearby), it seems like libraries were often situated near these spaces. Unlike Herculaneum, where organic material like papyrus survives, Pompeii lacks such evidence. Nonetheless, the Tablinum could have been a site of learning and study.

Likewise, this room was also likely a site for negotiation (from the Latin negotium or work) and commercial activity. Wealthy landowners conducted business from their home, and thus certain areas of the domus — like the fauces, tablinum, and atrium — were meant to be experienced by an audience of potential partners and clients. Whereas these spaces are likely to be considered ‘private’ in the modern world, our social norms do not map particularly well onto the ancient world in this case (and many others).

The Peristyle Courtyard: Luxury and Labor

Beyond the tablinum and other quarters, we often find a second outdoor space, a garden (11). Many gardens feature a peristyle, or column-lined porticoes beyond which further rooms are situated. Some gardens had elaborate water features in the center, while others were carefully curated assemblages of pungent plants and delectable produce. Of course, some gardens were combinations of all of the above!

Having a garden in the center of a city was a show of wealth. Owning green space afforded access to leisure and spectacle. We can envision these spaces as a curtain, a rural fantasy disguising an urban setting. However, such environments also facilitated food production and independence from local supply chains. In some cases, gardens could have even supported a proprietor’s business endeavors. While it is challenging to reconstruct ancient gardens, we can look towards some surviving paintings for a potential idea of what they might have looked like.

In this unprovenanced fresco from the Naples Museum, we get a sense of the sheer quantity of flora and fauna that occupied the Roman garden. Shorter greenery sways in the wind, as a larger fruit tree blossoms. Bright white and red flowers are interspersed between them. Below the greenery, a blue bird perches on a wooden trellis. Meanwhile, smaller songbirds hide within the tree. This small fresco gives us an idealized construction of these garden spaces, but turning to the archaeological record reveals other details.

The archaeological record preserves evidence of water features, like scalloped marble fountains and piping systems (12). Likewise, the popularity of ollae perforatae, perforated planting pots, reveals that specific species of plants were intentionally acquired and nourished in their infancy to produce such gorgeous garden arrays.

Clearly, a luxurious Roman garden demanded a lot of labor. Roman gardeners, the topiarius or viridarius, were trained with specific skillsets. The upkeep and working of a garden space was likely delegated to enslaved people. While representations of gardens and outdoor spaces conceal the manual labor that underlie such beauty, in a tour of the Roman domus, we cannot forget this unspoken truth. Enslaved people did not only work in the garden. For example, they were also tasked with record-keeping and serving meals. There is much more to be said about the lives and labor of enslaved people in the Roman domus, but that too deserves its own treatment.

Triclinia

The Romans loved to dine. Their banquet, a counterpart to the Greek symposium, was called a convivium. Typically, these sumptuous dining rituals occurred in triclinia (6). As we discussed earlier, the Roman domus was a site of negotium, or business. The convivium was also a site where business and politics could come to the fore… You might say that the triclinium was the ‘room where it happened.’

In the early empire, dining rooms were usually furnished with three rectangular couches, or triclinia, arranged in a U-shape. Guests and hosts reclined while passing around cups and reaching towards large serving plates at the center of the setup. Women and men were welcome at these gatherings, and meals were prepared and served by enslaved people.

Triclinia were often — but not always— situated with some access to exterior space, like the garden. Some examples were even located in the central area of an outdoor space. Thus, the experience of the garden was extricably linked to the smells, scents, and sounds of nature and even cacophonies of adjacent streets and alleys.

Meanwhile, these spaces are often defined by elaborate visual programs. In one of the newly unveiled houses in Regio V, the House of the Thiasos, we find a dark, elongated room. At first glance, the overwhelming presence of black walls seems simple. However, a closer look reveals a density of rich details. Female figures act as architectural supports below jewel-adorned columns. At the center of the largest black walls, we find mythological vignettes, like Cassandra and Apollo.

Although the room may seem austere. Under flickering candlelight, we can imagine that such a composition created drama and intrigue. With the looming doom of Troy evoked by Cassandra, we can also think about the philosophical and political conversations inspired by the visual program. Triclinia were intended to promote conversation and provide entertainment, acting almost like a stage for one of the Romans’ favorite pastimes.

Kitchens, Latrines, and Rooms Galore

Of course, Roman urban domi came equipped with practical spaces too. Kitchens and latrines (9) appear near each other within the home due to the shared need for water and drainage. Archaeologically, kitchens are often identifiable from the presence of ovens and cooking ware. Meanwhile, latrines are standard in form… it is hard to miss a toilet!

We often find domestic shrines in kitchens. Some scholars suggest that these were the shrines used by enslaved people. While others tend to think that this placement was more practical. In terms of practicality, this placement shortened the pathway between food and offering spot, while confining pungent odors and burning pits to one place within the home. Scholarly debates aside, kitchen-bound altars again encourage us to dissolve modern distinctions between secular and sacred when we think about the Roman home.

Unsurprisingly, there are many more rooms in the Roman domus— Oeci, Cubiculae, Aulae, et cetera. Rooms were used for sleeping, hosting, reading, playing, working, making, storage, worship, and much more. Some domi, especially suburban ones, had commercial zones for producing and storing goods, like wine.

There is much more to be said about the Roman domus! For example, this post skips over the rich work of Vitruvius, who tells us all about proper proportions, lighting, and arrangements of the domus in early imperial Rome. If you want to know more about the Roman house, let me know in the comments, and be sure to subscribe for notifications about future posts!

Great post. It is perfectly all right to mention that you took the photos. For the Boscoreale treasure, since photographing silver is a nightmare, using the Louvre website pictures is fine.

Using your images in Pompeii and Naples is another way to tell your readers that you are there, and know what you write about.

I do that with my own Substack; most of the photos there are pictures I took.

This was very fun! Thank you for sharing it. Though not Pompeii, I remember being struck by the standing remains at Ephesus when I visited 10+ years ago: it was so striking to me that something so ancient could remain relatively intact enough for me to feel like I was genuinely walking in the footsteps of ancient peoples! Very envious that you've had the opportunity to work at Pompeii; it sounds like the archaeologist's dream! Hope you enjoy it.