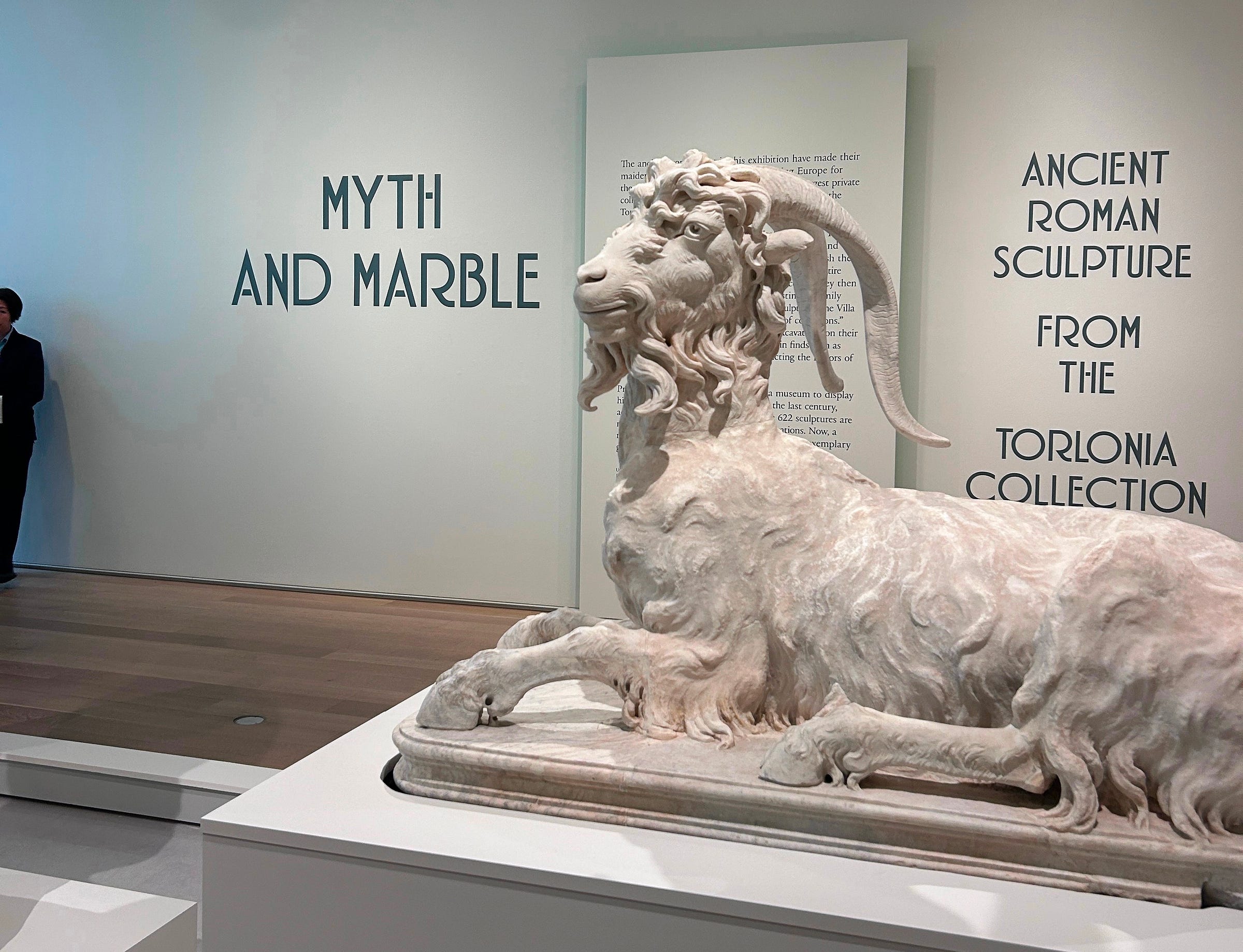

For the first time since World War II, an infamous group of ancient Mediterranean sculptures has been conserved, studied, and displayed with a traveling exhibition entitled Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection. This exhibition opened at the Art Institute of Chicago but will later travel to San Antonio and Montreal.

Let’s start with some collection history. These marbles (and others) were amassed by Prince Giovanni Torlonia and his son, Prince Alessandro, during the late 18th and 19th centuries. The works themselves are dated between the 5th century BCE and the 4th century CE, so we’re talking from Classical/Imperial Athens to Constantine, from Paganism to early Christianity, over 900 years of ancient sculptural production. They were on public display in Italy before the Second World War, and since then… many have not been seen. Indeed, these sculptures have never before left Italy.

Without further ado, let’s head into the exhibition… the titles I use here are my own, not borrowed from the museum by any means…

Introduced by ICONS

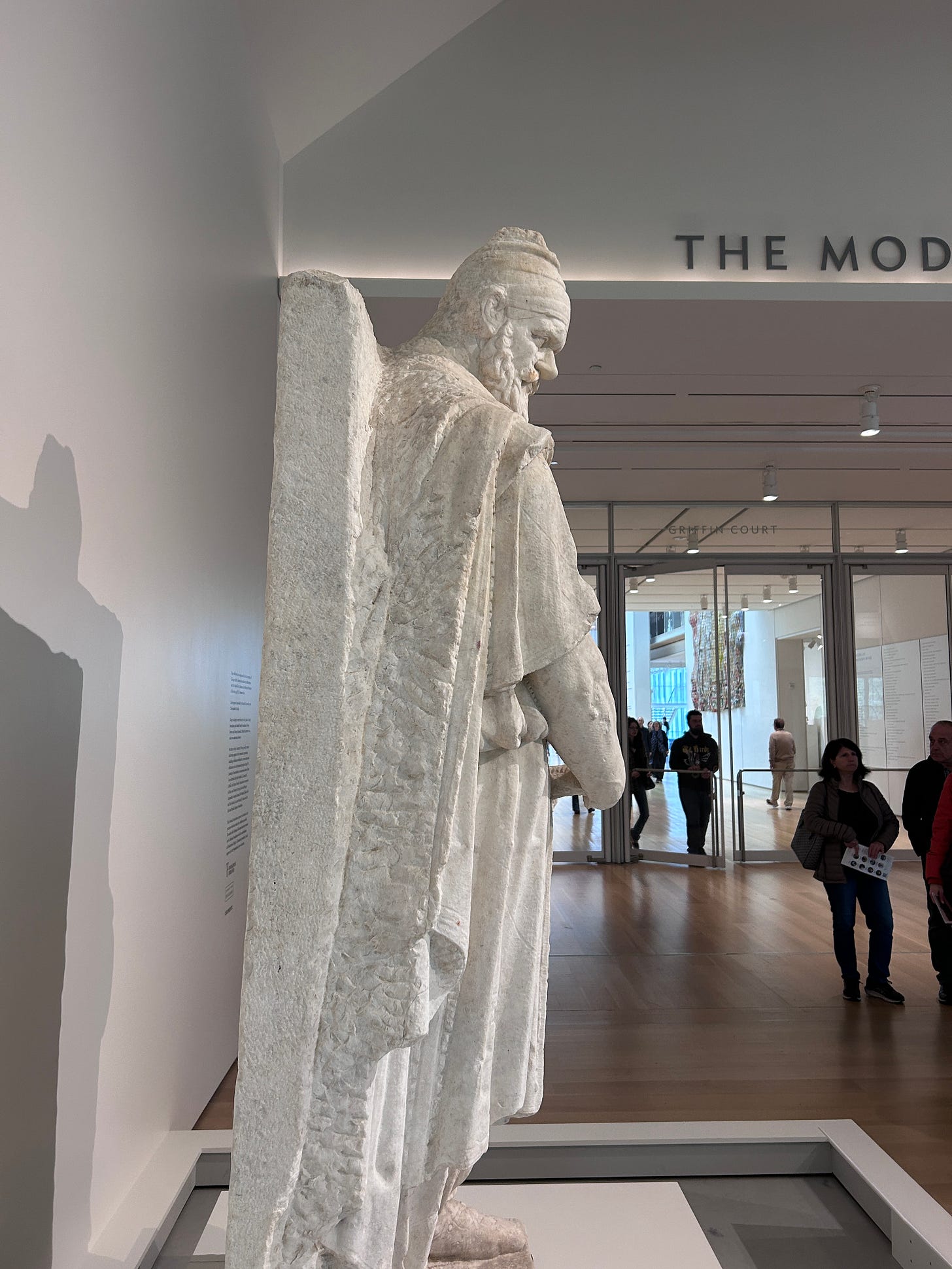

Before you turn towards the special exhibition galleries, you are funneled through one of the four halls of the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine galleries at the AIC. Here, visitors encounter a handful of ICONIC sculptures. Here I’ll discuss the Unfinished Dacian as myexample These works are all figural and indeed art historically iconic. However, I also use iconic not in the art historical way, but in the Gen Z way…

This monumental marble sculpture depicts a captured Dacian. His hands, now lost, were once bound. His weight sits on his tense right leg, with his left knee gently bent. He casts his eyes downwards and wears a distinct, foreign hat. There is no mistaking that this man is not Roman.

After conquering Dacia in 106 CE, Trajan made sure that everyone in Rome (and their best friends elsewhere) were well aware of his conquests. His legendary deeds were entrenched in a narrative on the column of Trajan, his eventual grave. Meanwhile, captured Dacians were used to adorn the halls of his forum and libraries. There are a handful of comparable sculptures that once stood in Trajan’s forum across Rome; two were used as Spolia on the Arch of Constantine (4th century CE), and two flank the entrance to the Casino Aurora, former home of the Boncompagni Ludovisi family (also in Rome).

Now, as an art historian, there is something particularly interesting about the figure on display in Chicago… it is not finished. Close inspection of the statue reveals a mass of visible chipping. Plus, chances are that this form was meant to be fully detached from the marble plinth behind. The hand of the sculptor is visible; we can almost imagine him working away at the rough surface after painstakingly excavating the figure’s face and body.

This tells us something important about the process of sculpting marble. The figure is worked from a monolithic fragment, but not wholly detached from excess bulk until the form is nearly complete. However, this peculiarity also presents a mystery of sorts. We do not know why this statue was never finished. We do not know exactly where he was meant to go. We can only imagine and remember that our modern knowledge is obscured by time, space, and context.

Imperial Portraiture

Now we enter the first of two exhibition galleries. On your right, you are greeted by a family tree of the imperial dynasties: The Julio-Claudians, the Flavians, the Nerva-Antonines, and the Severans. Unsurprisingly, their portraits line the walls. In addition to the wide array of busts, or portraits of the chest upwards, we find a few full-body portraits.

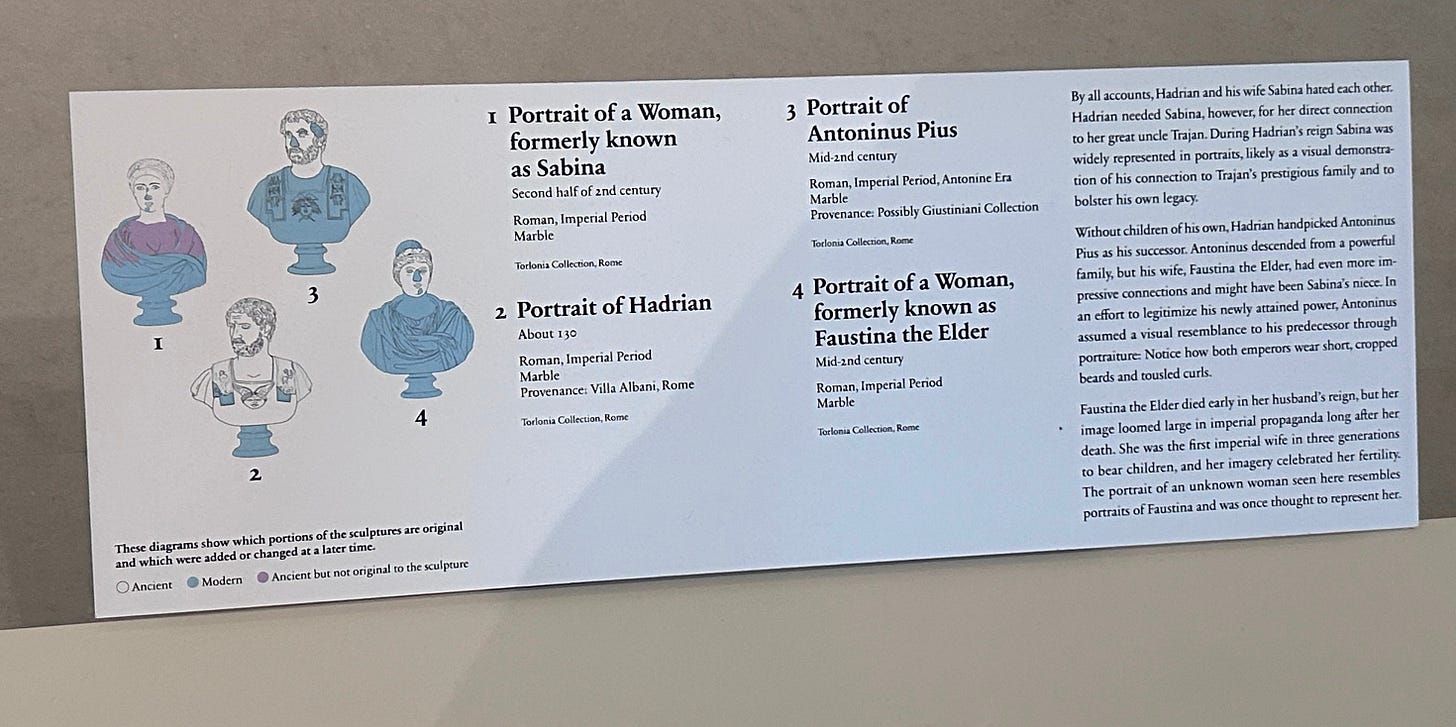

Identifying the emperors of the early and high empire is quite easy. Their visages were often accompanied by inscriptions and were plastered everywhere. However, the same cannot be said of imperial women. Indeed, the exhibition plays with portrait identifications. The women are presented in the exhibition as they were identified by their early modern collectors; however, curators note that many of these women have since been identified as anonymous wealthy women.

Early modern collectors were invested in assembling encyclopedic collections that acted almost like a family photo album for each dynasty. They were so desperate to collect and capture imperial lines that they found portraits of random women and named them accordingly. This perhaps reflects a twofold problem. First, the people contributing to early artistic canons and historical narratives were not invested in the accurate and rigorous histories of imperial women. Second, so little of these women survives in the historic record that identifying and naming them is impossible for modern actors.

Thinking about modern engagements with incomplete historical records does not stop with gendered histories. Indeed, this exhibition does a brilliant job of reminding us that seemingly complete ancient sculptures are often pastiches of new and old. Each label highlights how much of each statue is original, ancient repairs, or modern repairs. What at first glance seems to be a complete, ancient work is often almost entirely modern. Check out the label for these four figures thought to be from the Nerva-Antonine dynasty below.

Sometimes it can be quite easy to spot repairs. On Antoninus Pius, the third figure from the left, we see a seam between two shades of marble along the figure’s neck. Do you think that these repairs are easy to spot?

Before moving to the next room, let’s think about the aesthetics of these repairs. So to some of us, these repairs may seem obvious. This was certainly true for the early modern patrons of these repairs who displayed these statues in personal museums. However, a complete bust (even if mostly modern) was preferable to a fragmented head. Visual completeness mattered more than authenticity. One of my favorite parts of this exhibition was how well it navigated this issue, reminding us that values change over time… and that’s an essay for another day!

Marble Beyond Earthly Life

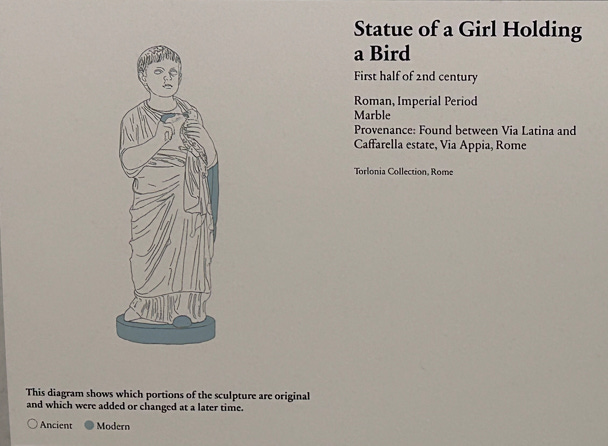

In the next room, the exhibition explores how marble sculpture is used to communicate beyond earthly life, particularly with the realms of death and divinity. Funerary art always resonates with me; it draws us in and reminds us of the potent, personal power of images. This was especially true of a portrait of a young girl enveloped in her dress, clutching a small bird to her chest.

It is quite popular for young children to be represented with birds in funerary imagery. Chances are that this young girl died, and her family erected this statue as part of a larger commemorative monument so that they might visit her and pay homage to their daughter and other deceased ancestors. These portraits allowed grieving families to mourn and later remember their loved ones. Museums often sanitize these emotions, pulling these objects from their ancient, agoniizng contexts.

Speaking of interment, one of the most spectacular objects in the show is a monumental arcade sarcophagus featuring the labors of Hercules with a reclining couple on its lid (yes, the husband’s face looks a lot like Hadrian!). In each niche, we find the legendary hero completing another one of his labors. On the left, the nude hero fights the Nemean lion while his club seems to float in the air. Thereafter, he holds the lion’s skin while fighting an array of enemies.

In each vignette, he is posed dynamically, nearly in motion. You could imagine that as people walked around the Sarcophagus, the figures seemed to move, enacting the heroic labors and earning his salvation. The lively figures contrast with the peaceful, reclining couple above. Married in life, they live on together for eternity on this monument, accompanied by putti or cupids. Marble mediates between life and death, memory and loss, motion and stillness.

‘Textbook’ Objects

Finally, we come to the final room of the exhibition, where we encounter what some may call ‘textbook objects,’ as in an assortment of unique sculptures that I have seen reproduced again and again in textbooks and publications, but never in the flesh.

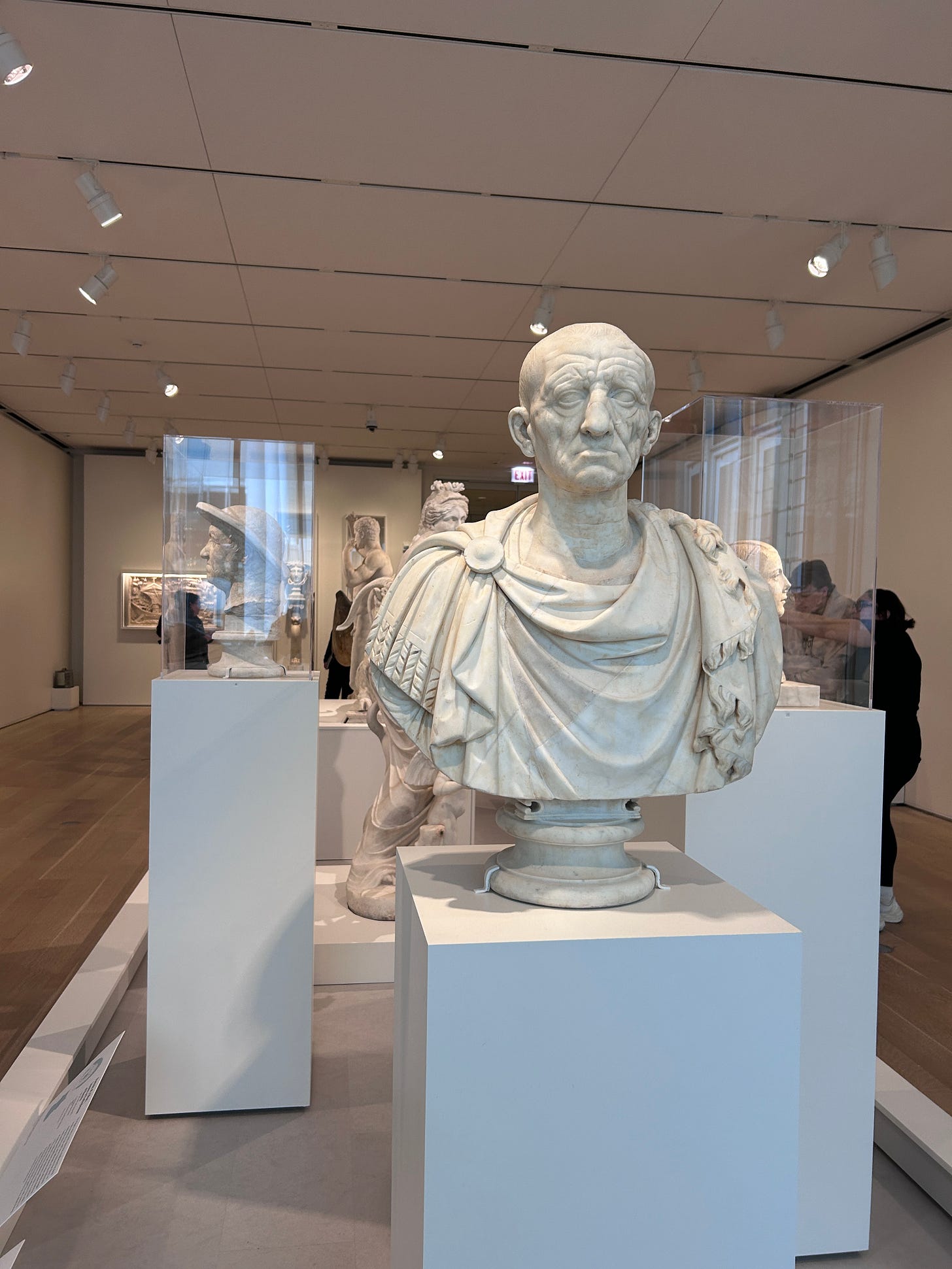

I studied this portrait for the first time as a junior in high school. This is the iconic Patrician from Otricoli. His face is truly ancient, but the rest of the bust is not. Unlike the idealized emperors we saw earlier, this figure is depicted in a veristic style, which means that his age is visualized, even emphasized through heavy wrinkles and deep-set eyes.

Between the Republic and Empire, changes in portraiture styles accompanied changing tides of political structures and priorities. Under the republic, to keep it simple, age meant wisdom, and wisdom made a man a great senator. However, starting with Augustus, who consolidated political power and claimed divine patronage, portraits of leading public figures became perfect, ideal, and classically beautiful (to make an oversimplified claim).

While there is so much more to be said and explored in this exhibition, this marks the end of today’s newsletter. Myth and Marble was such a joy to explore, and it gets us thinking about how much of our knowledge/assumptions about marble in antiquity is perhaps founded on modern myth.

What questions do you have about the exhibition? Roman sculpture? Please share them and any of your thoughts below!

Loved this review & analysis!! So many great pieces on display. Wondering if the museum mentioned if statues were originally painted/coloured, or if the focus was on the marble as material/medium solely?

What a great write-up! I'm particularly drawn to the unfinished sculpture you discuss. It almost has an eerie quality to it, especially that side view. It makes me ponder the process of making sculpture out of marble and the qualities of the medium, in a way a finished sculpture might not!